Climate Friday | Cut, Carve and Rebuild at 76 Southbank

6 August 2025

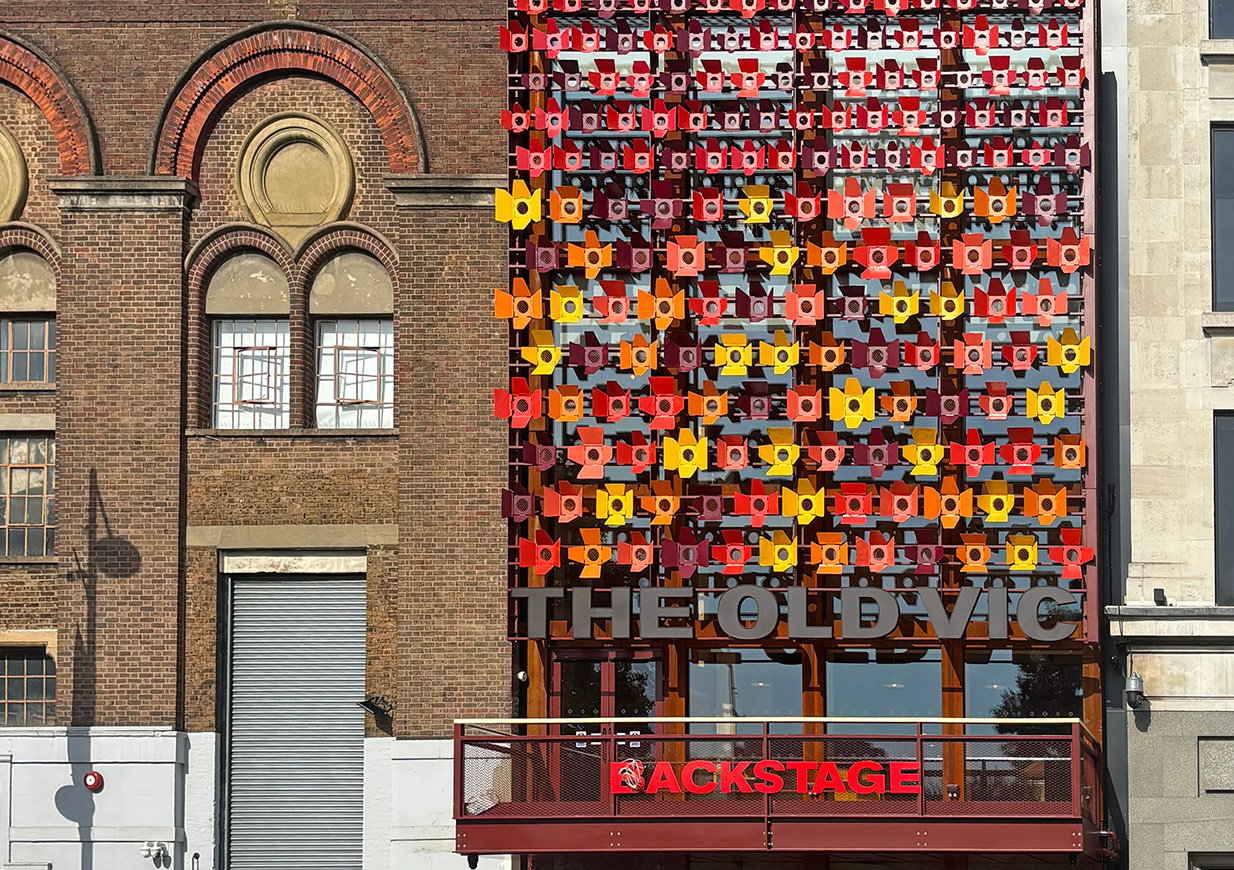

76 Southbank is a landmark adaptive-reuse project situated on London’s South Bank. The scheme sensitively refurbishes and extends a Grade II-listed building originally designed by Sir Denys Lasdun in the 1980s. Led by AHMM for client Stanhope, the £140 million development transforms the former IBM headquarters into around 420,000 sq ft of modern, flexible workspace with strong sustainability ambitions. Eckersley O’Callaghan has been involved from 2019 through to practical completion, providing specialist facade engineering to support the delivery of this £18 million facade package and help realise a low-carbon, heritage-led retrofit.

The Brief

Often overshadowed by its famous neighbour, the National Theatre, the building is one of Denys Lasdun’s lesser-known works. Although prominently located on the riverfront, it never fully engaged with the public realm. Its slender rectangular form turns a narrow face to the Thames, while long terraces and ribbon glazing define the elevations.

Before refurbishment, the building had effectively become a stranded asset. The terrace balustrades no longer complied with building regulations, making external spaces unusable. Extensive single glazing, low ceiling heights and ageing fabric left the interiors dark, cold and inefficient.

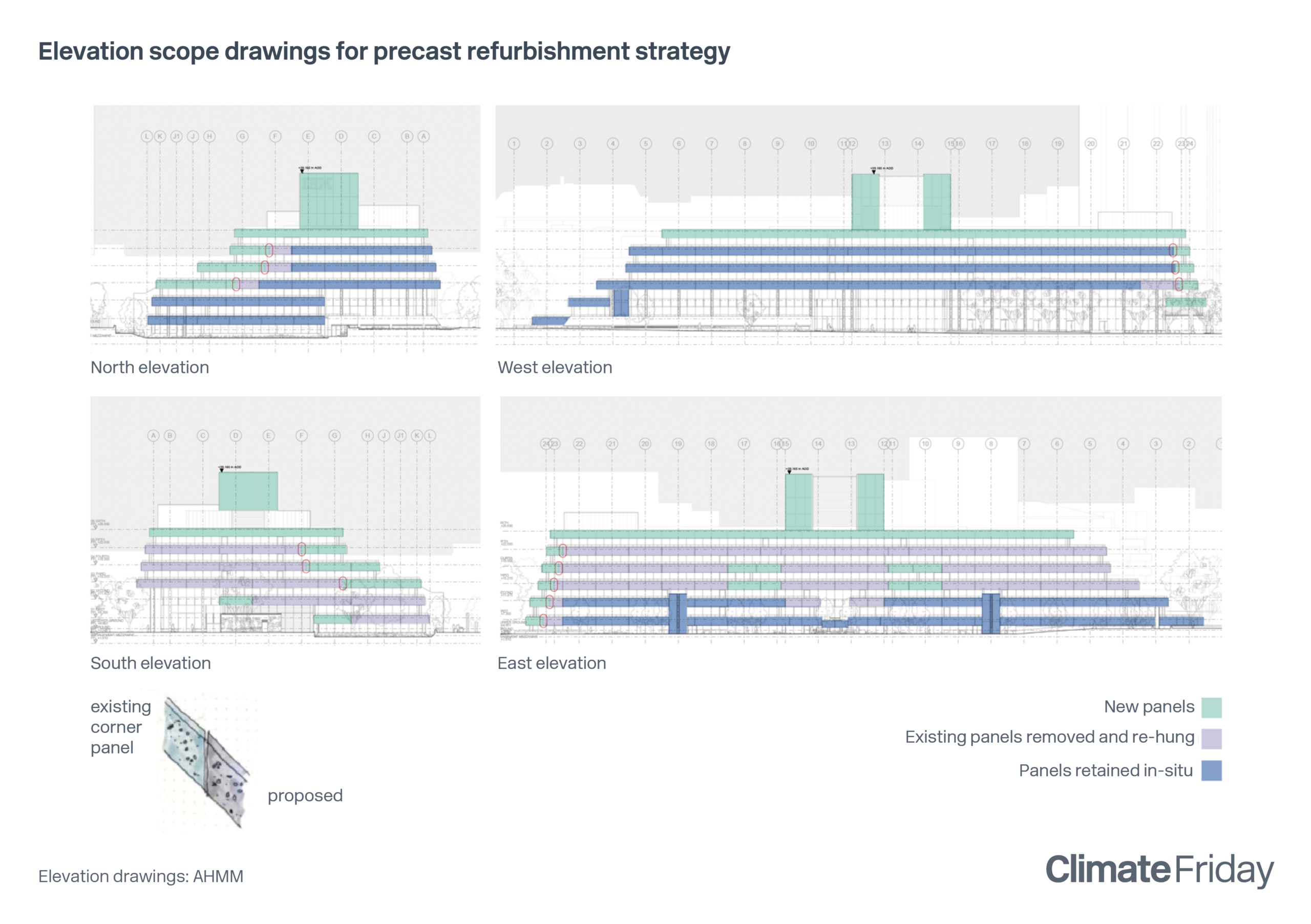

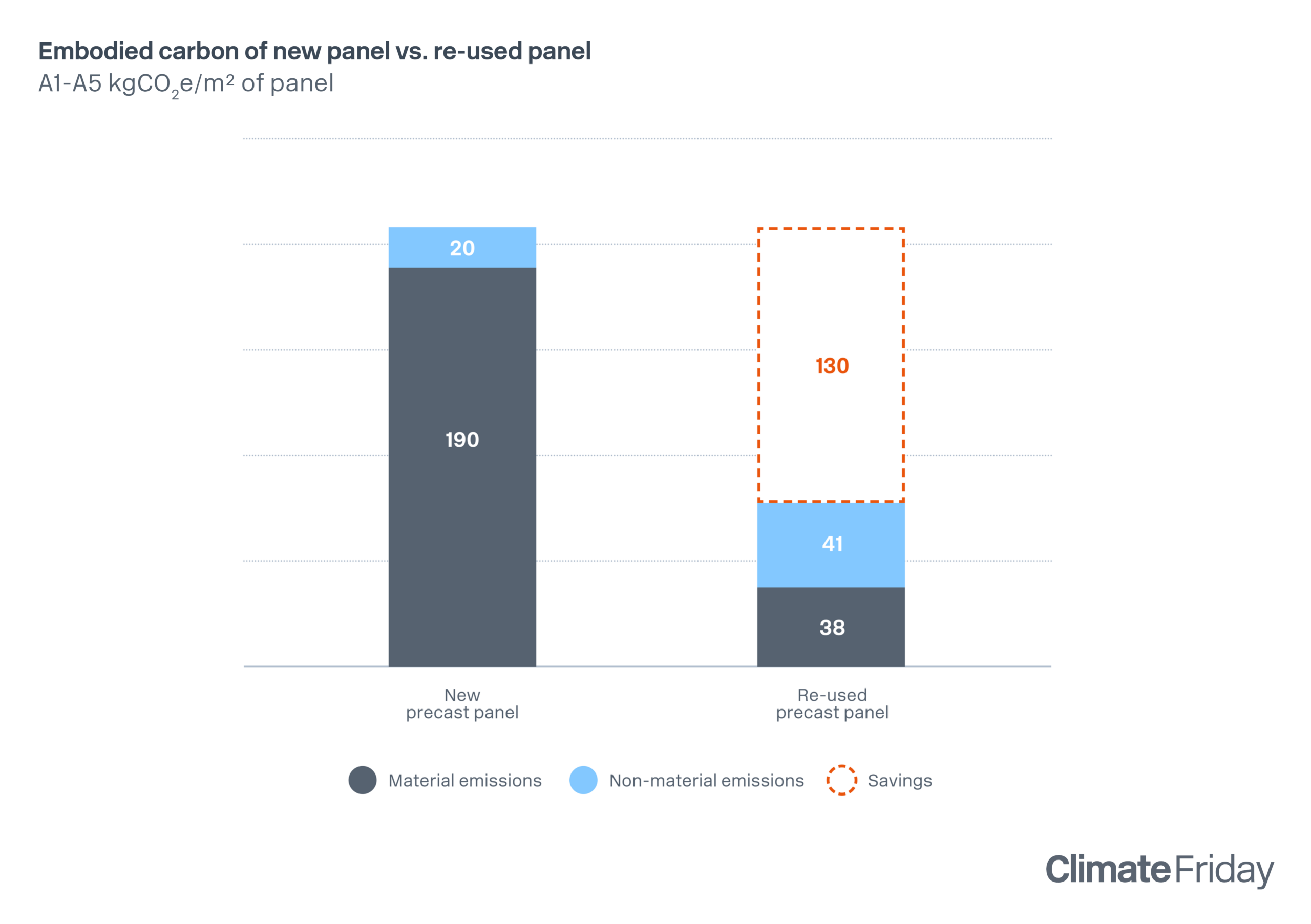

AHMM’s design sought to complete the vision Lasdun could not fully realise in the 1980s. The proposals extended the eastern floor plates and introduced a new sixth floor, unlocking valuable space and improving performance throughout the building. Central to this transformation was the careful removal, restoration and reinstatement of 101 precast balustrades, each measuring eight metres in length. This strategy enabled an embodied carbon saving of 130kgCO₂e/m² of facade surface area compared to using all new precast balustrades.

This case study explores how a disassembly-led approach enabled the project team to retain original material, significantly reduce embodied carbon and extend the life of one of London’s most distinctive facades.

The Process: Concept & Schematic Design

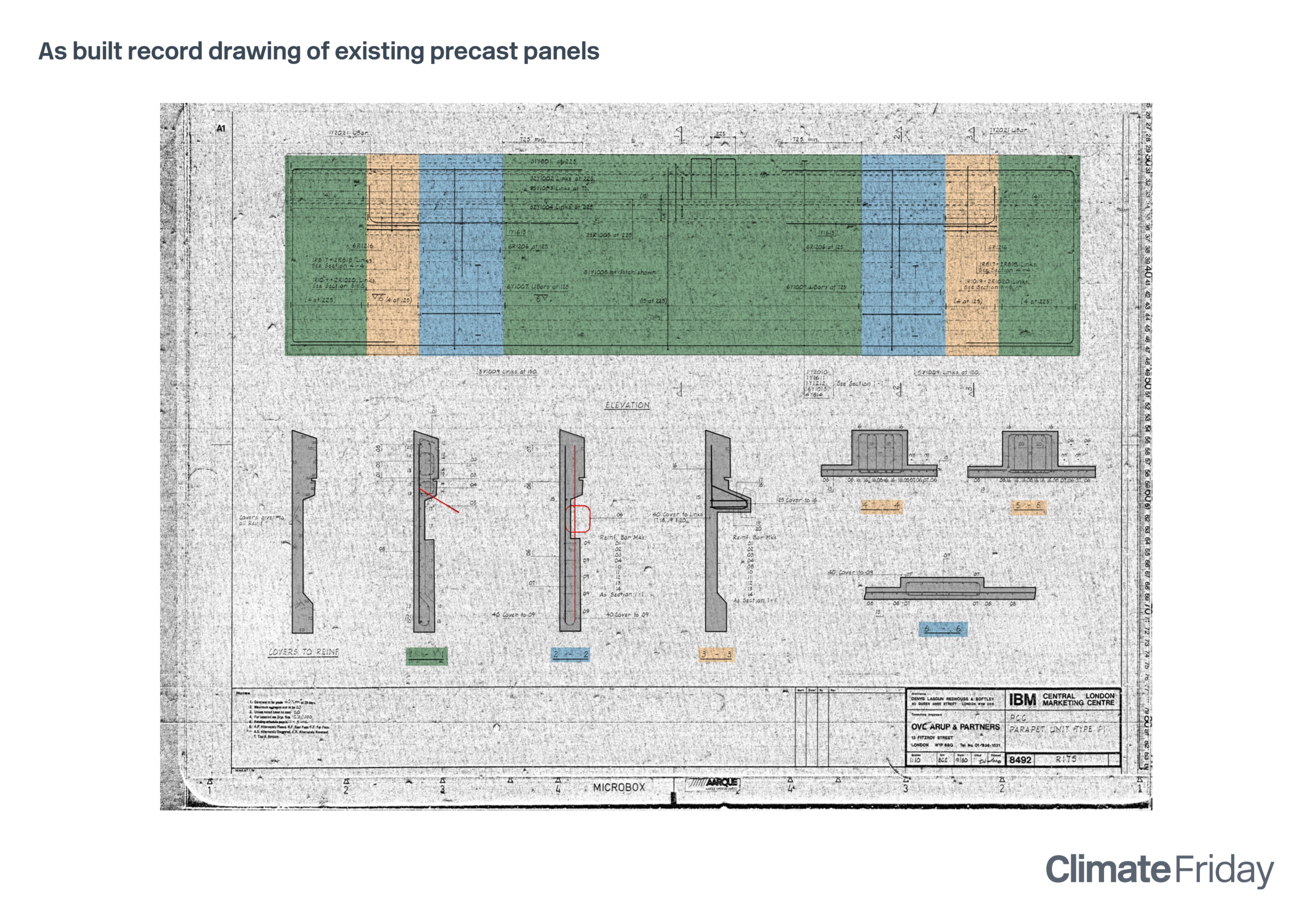

From the outset, our focus was on understanding the building as it was originally conceived. We reviewed historic as-built drawings, commissioned condition surveys and assessed the long-term performance of the precast balustrades to establish whether a viable strategy for reuse could be achieved.

We even tracked down the original precast manufacturer to better understand how these elements had been made forty years earlier. The balustrades, handcrafted by Marble Mosaic, were a defining architectural feature, and each comprised a hand-seeded precast unit supported by reinforced concrete corbels, with shear links cast directly into the terrace slab.

Unlike modern aluminium curtain wall systems, which can often be dismantled relatively easily, these balustrades were fully integrated into the structure. Each panel weighed several tonnes, and the original lifting points had long since been grouted in and rendered unusable. With no structural calculations available in the archive records, it was unclear how much the balustrades contributed to the stiffness of the slab, or how the slab itself affected the behaviour of the panels.

The key questions were therefore simple but critical: could the panels be safely and economically separated from the slab, lifted out without excessive damage and reinstated in a way that met modern performance expectations? And, after all that effort, would the reality on site match what we anticipated from the drawings?

These risks were communicated early to the client, alongside the need for targeted surveys and material testing. At the time, large-scale refurbishment of this kind was still relatively uncommon, which placed even greater importance on getting the design intent right before the main contractor was appointed.

The Process: Technical Design

As the design developed, our focus shifted to validation and coordination. We worked closely with the survey team to interpret findings consistently, defined the scope of repairs and strengthening works, and reviewed demolition and precast contractors’ proposals to ensure that removal, storage and reinstatement could be managed safely. Testing played a major role in this phase, with pull-out and shear tests carried out to confirm the performance of the new bracket design.

A materials engineer undertook extensive core drilling to assess the condition of the concrete, the performance of the aggregates and the likely remaining service life of the precast units. In the absence of original structural calculations, one of our biggest challenges was understanding exactly how the balustrades interacted with the slab. On drawings, the distinction between structural concrete, screed and prefabricated elements can appear clear. On site, it is far less so. After numerous investigations, the slab began to resemble a rather architectural version of grated cheese, but the effort paid off and we were finally able to confirm that the precast panels were suitable for reuse.

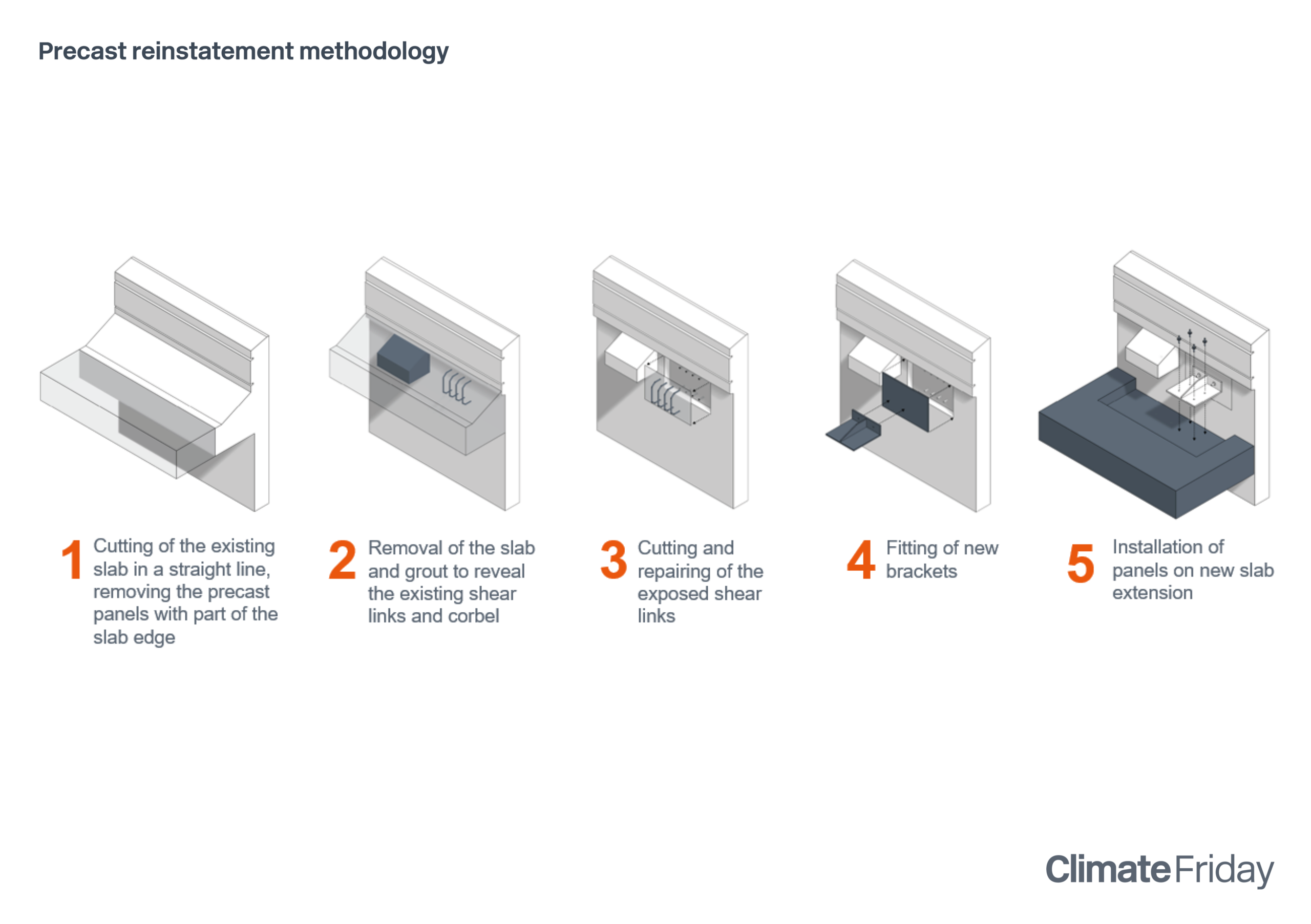

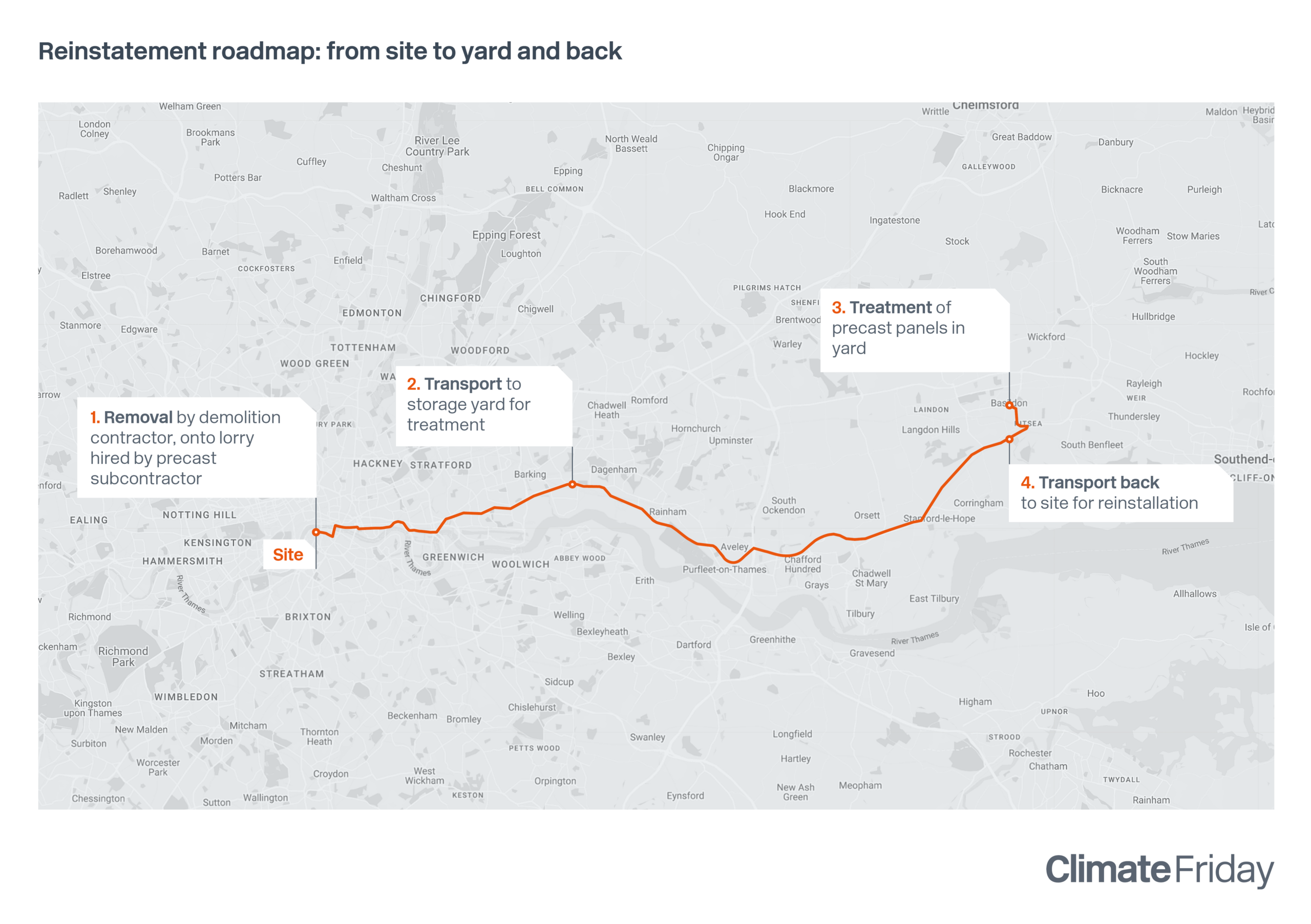

The agreed removal strategy involved extracting each balustrade together with a 400mm slice of the terrace slab. These composite units were transported to an off-site yard, where controlled cutting sequences allowed the visible faces to be preserved. The original corbels and shear links were then carefully adapted into new bracketry, compatible with the extended slab and the building’s updated structural strategy.

Design Responsibility

Early discussions with the client were essential to align expectations around service life, warranty coverage and the distinction between “new” and “retained” elements. This clarity helped define responsibilities across demolition, precast and facade workstreams and avoided ambiguity as the project moved into delivery.

One of the key commercial discussions centred on warranty scope. Given the reused nature of the balustrades, it was agreed that warranties would apply to structural integrity rather than full system performance, reflecting both the realities of refurbishment and the ambition to retain original fabric wherever possible.

The Result

If you stroll past the National Theatre and glance toward the other concrete icon next door, you’ll likely spot the subtle differences between refurbished and new balustrade panels. This is our honest way of saying it’s a refurbishment, not a recreation and achieving a perfect colour match simply wasn’t possible. Even though the team tracked down the original quarry, the aggregates had changed over forty years.

Striking the right balance between what could realistically be cleaned in such a busy location and what needed renewing resulted in a playful, textured collage of old and new that tells the story of the building’s evolution.

Florence’s Lessons Learned

Flexibility is essential when working with a mix of retained and new elements. Ensuring that both share the same support strategy makes future maintenance and replacement far simpler, and avoids headaches when a damaged unit needs to be swapped out.

Early planning of logistics and storage is equally critical. Large, fragile historic components demand careful choreography between demolition teams, main contractors and facade specialists. Each party joins the process at a different stage, yet their work must interlock seamlessly, like pieces of a particularly heavy jigsaw puzzle.

Above all, the project reinforced the value of the original design. Despite changing standards and technologies, older buildings often embody exceptional craft and thoughtful detailing. Taking the time to understand this legacy is key to unlocking meaningful, sustainable reuse and ensuring that refurbishment is not just an upgrade, but a continuation of the building’s story.

Written by Florence Li.

Photography © Rob Parrish