Rethinking the Need for New Buildings

17 January 2024

Do we really need another new building?

This is always the first – and most important – question our engineers ask when looking at development opportunities on sites with existing buildings. Thankfully the climate emergency is changing the mindset of the construction industry away from the unfortunate ‘cult of the new’ to recognising the value of our existing building stock and the sustainability benefits of adaptive reuse and refurbishment.

The last two articles in our adaptive re-use series introduced and examined the challenges of adaptive re-use, and in this article we get into the detail of facade refurbishment.

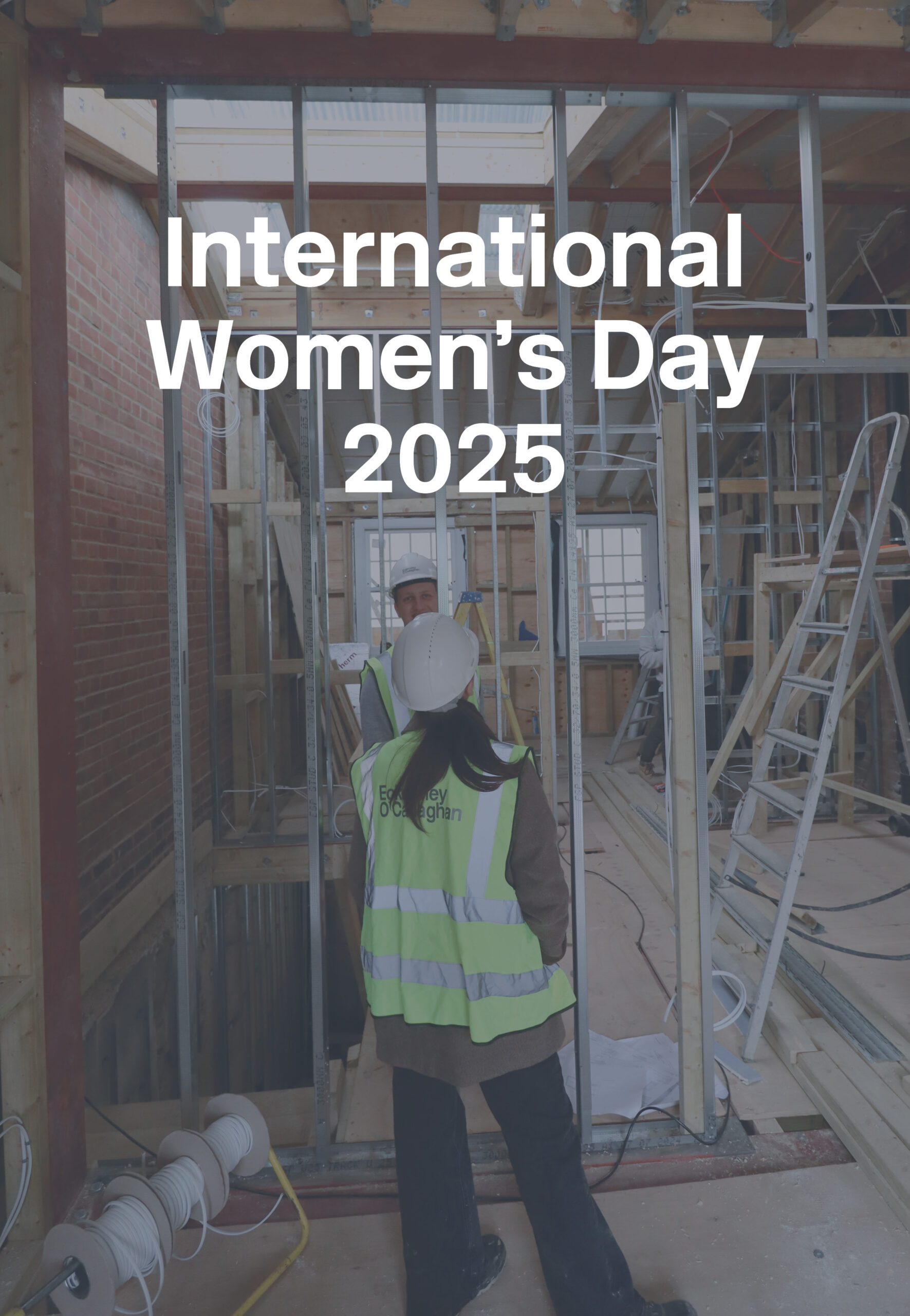

Eckersley O’Callaghan’s specialist Facade Engineering group has a strong track record in adaptive reuse and refurbishment projects, including sensitive heritage buildings. We are honoured to be leading an initiative with the CWCT (Centre for Window and Cladding) to produce a new sustainability guide to facade refurbishment, in collaboration with fellow consultants, clients, contractors and specialists.

Reasons for facade refurbishment

Reducing carbon emissions and our impact on the environment is the overriding reason we advocate adaptive reuse, however there are several practical reasons clients may need to consider existing facade refurbishments: Components within a building facade system have failed; a heritage building that needs to be conserved; a need to upgrade internal performance or bring a building structure in line with new regulations; a change of use; or a client’s desire to improve the value of a commercial asset.

Conserve or replace?

Whatever the reason for considering facade refurbishment, there will be a tug of war to manage between conservation groups at one end and ‘build new’ proponents at the other. Neither option is simple and compromise is inevitable. This is why we push for early involvement at RIBA Stage 0 to put any external pressures to the side, and focus in on the practicalities and sustainability.

Early engagement is essential

At RIBA Stage 0, the most pressing questions every facade refurbishment project brief asks are; why does the existing building need a refurbishment? What requirements doesn’t the building meet? Is the building energy efficient, and can it achieve net zero carbon sustainability goals? Only a facade refurbishment specialist can effectively investigate, challenge, and answer these questions to help form a viable detailed brief that takes the project into Stage 1. This is dis-similar to new-build projects which often appoint specialists at RIBA Stage 2 or 3, so it’s often an unfamiliar approach to clients.

For our specialists to undertake a purposeful assessment of the various options and develop the best approach at this early stage, the following considerations are particularly important:

- A willingness to challenge the brief – Without early engagement, some client briefs can be uncompromising and unsympathetic to existing buildings, or geared towards new-build thinking . We are seeing this change slowly over time, but there still needs to be a paradigm shift in the attitude of developers and building owners towards the flexible adaptation of project briefs to embrace the character and parameters that an existing building facade often imposes on a refurbishment project.

- Knowledge of the building – Ideally building owners will have a good understanding of their asset and keep (and maintain) as-built information and maintenance logs; these are an invaluable resource when considering how best to upgrade a facade. However, in our experience this information is often lacking and therefore thorough and targeted surveys are a key tool in identifying the materials and systems on a facade, their condition and how they are performing.

- The right team – A holistic assessment needs a diverse team of consultants for effective decision-making. In addition to the early appointment of a facade refurbishment consultant, it’s also useful to engage specialist refurbishment contractors earlier in the procurement programme to help derisk the project and get the value of their specific expertise.

Establish what you’re working with

Once appointed, our facade refurbishment team undertake a process to understand the building facade components and how they come together, the refurbishment possibilities and parameters:

- Surveys – There are many levels of investigative building surveys, from the initial high level facade survey carried out at Stage 0 by a building surveyor, right through to the post-demolition survey at Stage 5. Our first survey would be a specialist scoping visual survey at Stage 0/1 and, if required, an intrusive survey at Stage 1/2, following up on the findings of the first high level survey. The purpose of these surveys are to get ‘up close’ to the facade, establish the component systems and hone in on any issues and defects.

- Establish condition and performance – The building surveys will highlight facade defects such as; leaks, condensation, hazardous and inappropriate materials, solar control and overheating issues, poor ventilation, and compliance with modern safety codes. We record and rationalise these into manageable typologies such as workmanship issues, design issues and materials/system deterioration.

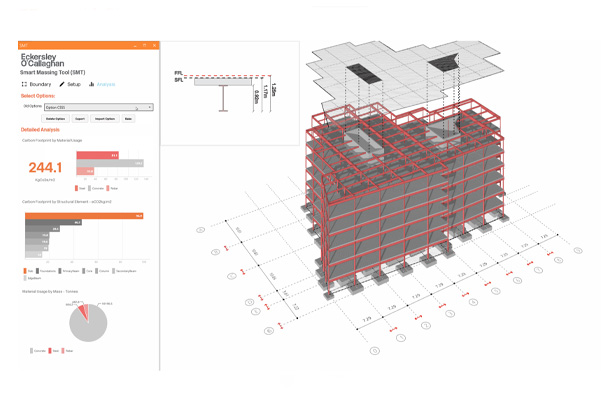

- Digital twin – Once the condition and performance of the facade has been established, we coordinate this existing performance with a digital twin, typically working with a like-minded M&E engineer, verified against metered data. We take a fabric first approach to analyse the impact on embodied and operational carbon performance of each strategic intervention, recognising that passive performance is key to achieving net zero goals.

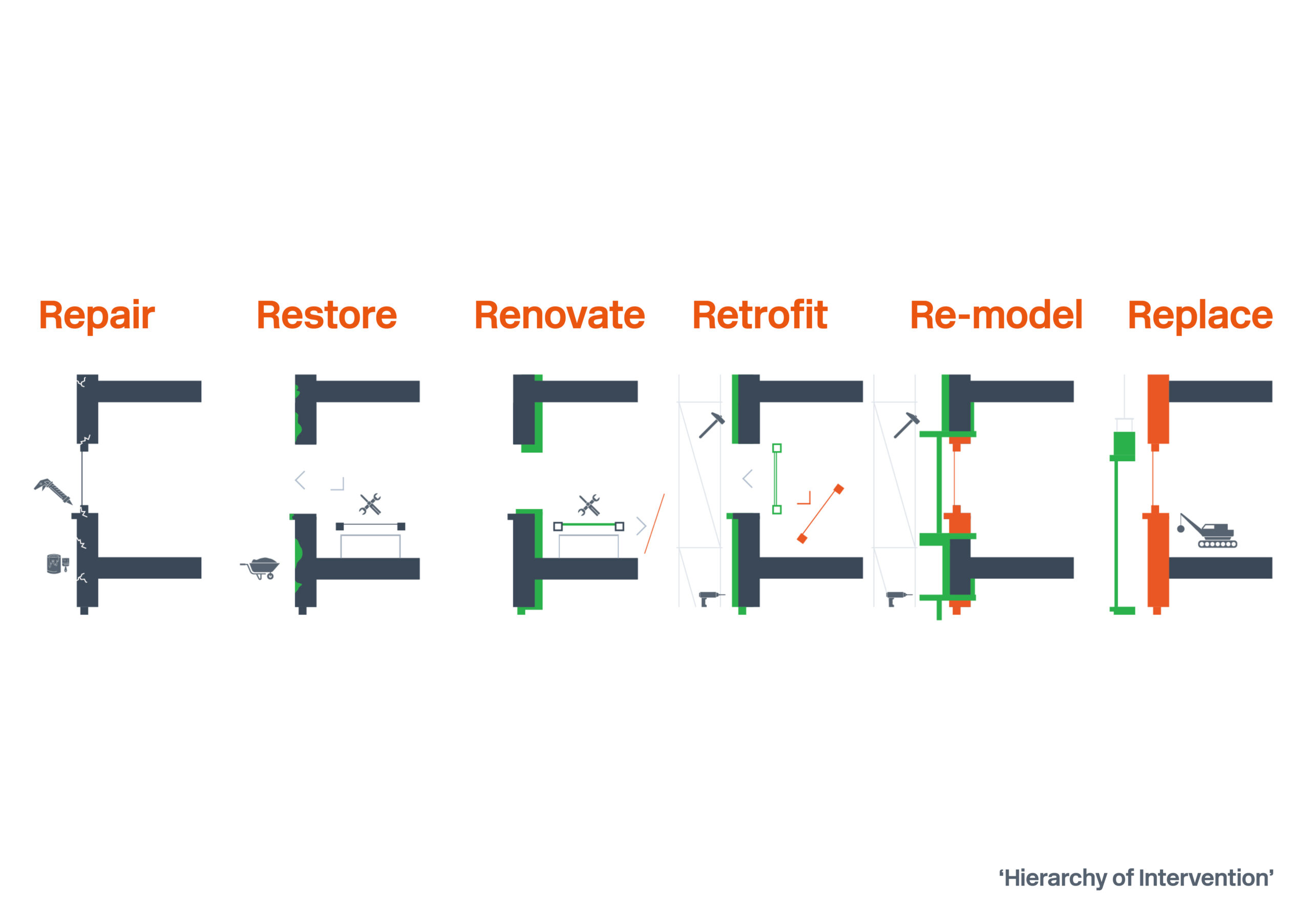

The hierarchy of intervention

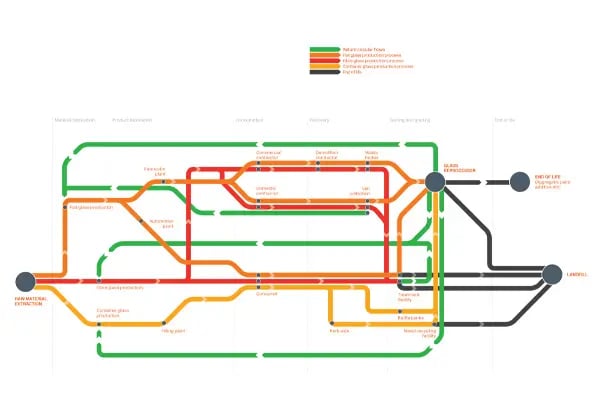

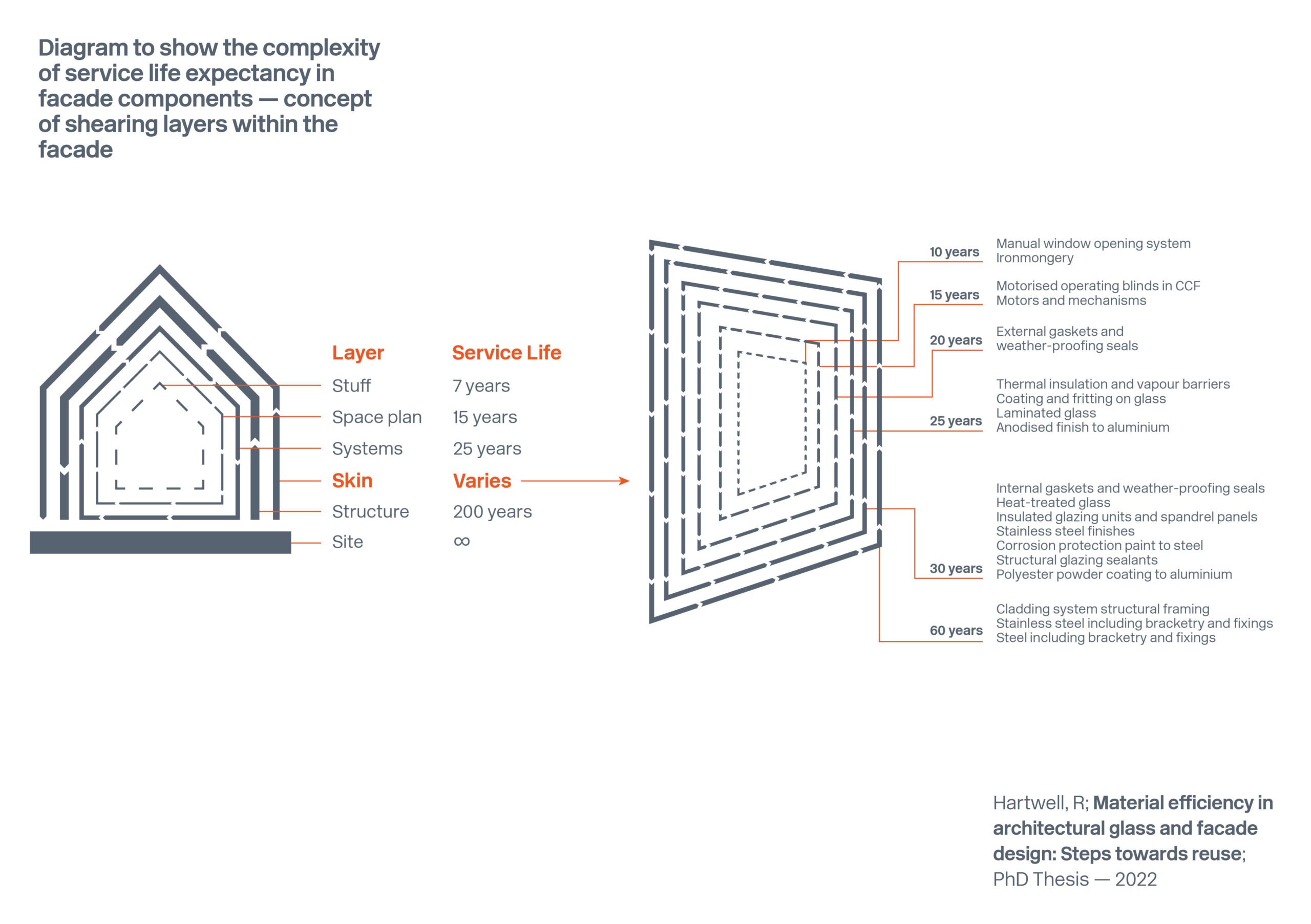

There has been a tendency in our industry to either patch repair or wholescale replace facades. But when considering the facade in the context of a building refurbishment, it represents a different ‘shearing layer’ to the structure and services. Service lives can vary vastly within a facade – from a few years to a few hundred years – with many components offering long life if adequately detailed and maintained. So there are many approaches we can take to a facade refurbishment which we’ve mapped onto a strategic ‘hierarchy of intervention’.

By example – for a non-thermally-broken single-glazed metal window, common to our building stock, the hierarchy of these strategic interventions would fall under:

- Repair / restore – Repairing and restoring the original windows back to their original condition would typically have little thermal benefit, but would temporarily improve airtightness slightly.

- Renovate – Upgrading the existing window system (ie replacing glass units and/or ironmongery) could yield a 30-50% thermal improvement, improved airtightness, and extend the window life considerably. But the windows may need to be removed if processing can’t be done on site, with the associated logistical and temporary works challenges.

- Retrofit – Fitting additional systems to compensate for poor performance (ie secondary glazing) would significantly reduce U-values but makes the need for ventilation tricky. Cold bridging and the potential for trapped moisture can also lead to accelerated deterioration.

- Re-model – Removing windows and improving the frame and glass (ie retrofitting seals or thermal breaks) is really limited to certain window types (ie timber windows) and can be commercially and technically unviable with metal windows and frames.

- Replace – Using a modern high performing window system can typically yield 60 to 80% thermal improvement. But original framing sightlines may need to increase and current systems are typically deeper and look a little heavier; both issues could pose an issue for heritage building facades.

A strategic balancing act

Establishing the most appropriate intervention strategy is not simple and involves a host of different parameters such as cost, programme, logistics and sustainability. The latter is always our focus and these are our key considerations:

- Whole life carbon – With facades typically representing 15 to 25% of the embodied carbon in the original building, there is a convincing argument to retain as much original facade material as possible, and conservationists argue this is especially important in culturally valuable buildings. However, this preservation needs to be done in balance with the need to upgrade the performance of our existing building stock to create lower operational carbon, safe and comfortable buildings. With our commitment to net zero carbon and the government’s Heat and Buildings Strategy (Oct 2021) we must reduce our use of fossil fuels, and a fabric first approach is required in most instances to achieve this. Carrying out whole life carbon analysis and optioneering studies to compare approaches across the hierarchy of intervention is becoming more commonplace as a key client driver, and an emerging planning requirement.

- Embodied carbon + operational carbon payback – Expanding on the last point and using windows as an example again, we use CWCT methodology to calculate the embodied carbon of each strategy and test the digital twin thermal model to establish operational benefits and payback. For example, refurbished windows may have the lowest embodied carbon, but they will need to be replaced in the future and have little impact on operational carbon. Whereas, replacing windows may create higher initial embodied carbon, but the carbon payback can be swift, resulting in higher whole life carbon savings.

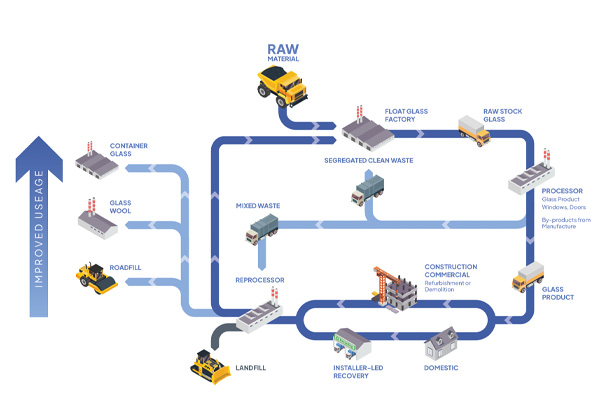

- Circularity – The retention or re-use of materials and systems in refurbishments is a positive contributor towards the circular economy, but not necessarily the most appropriate approach. Care must be taken to ensure material removed from buildings as part of a refurbishment is carefully studied (via surveys and testing) so it can be given the best opportunity to contribute to the circular economy. We are seeing and contributing to more pre-demolition audits, which identify the most appropriate methods of dismantle and ensure custody of ‘waste’ materials and systems such that they can be re-used or, as a minimum, recycled appropriately.

- Social impact – Building refurbishments can have significant social impact; not only on building occupiers (who may need to stay in place or be relocated), but also to the surrounding community. Where disruption can be minimised, it should be.

Holistic facade refurbishment

While carefully considering every strategic facade intervention at a component level, it is also imperative to take a whole-building approach to facade refurbishment. Improving one component or an aspect of performance in isolation can potentially be detrimental to other aspects of the building. For example, making an existing building airtight without addressing how ventilation works in the absence of natural infiltration can create air quality, condensation and mould growth problems.

We advocate for a holistic approach to facade refurbishment with input from the right consultants at a very early stage, in order to refine a brief, balance each project parameter and successfully navigate the push-pull between conservationists and new-build proponents.

Eckersley O’Callaghan credit: Hugh McGilveray

Adaptive Reuse Part 1

Adaptive Reuse Part 2